Abstract

Global health security depends not only on hospitals and laboratories but also on how societies produce, trade and consume animals. With 75% of emerging diseases originating in animals, strengthening animal health systems is critical to preventing spillover events such as Ebola, Rift Valley fever (RVF) or avian influenza. Within a One Health framework, which integrates human, animal and environmental health, animal health acts as the first line of defence, bridging global security priorities with local livelihood realities. This article explores two emerging pathways: animal waste surveillance and underrepresented threats of wildmeat value chains. Studies led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) demonstrate how abattoir waste can serve as low-cost, scalable surveillance tools, generating early warning for zoonotic threats and antimicrobial resistance. Leveraging tools such as genomics, the case study on RVF shows how genomic and ecological monitoring in livestock reveal patterns that allow preventive action before outbreaks escalate. Equally, research on wildmeat trade in East Africa highlights how informal value chains amplify risks by lacking regulation and protective practices, while being sustained by cultural and economic necessity. Addressing these risks requires community engagement and context-sensitive alternatives rather than criminalisation. Together, these insights demonstrate that advancing animal health systems is not simply a technical upgrade but a strategic investment in One Health security and global stability.

Global health security depends equally on how we produce, sell and consume food as it does on the biosafety practices in laboratories and the infection control measures in hospitals. It is estimated that 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin [1]. These diseases, which spread from animals to humans, or vice versa, include Ebola, Mpox, avian influenza and Rift Valley fever, which originate in animals and have become significant global health concerns.

In a world of rising biological threats, whether natural, accidental or deliberate, strengthening animal health systems within a One Health framework is essential. They form the first line of defence against pandemics and against vulnerabilities created by risky practices such as the consumption of wildmeat. Protecting populations by securing animal, human and environmental health together strengthens One Health security, emphasising prevention at the source, rapid detection of threats and coordinated response across sectors.

Why Animal Health Is Central to Global Security

The pathways through which biological threats emerge and spread are shaped not only by weaknesses in animal health systems but also by the ways communities interact with animals and ecosystems. Spillover, the term given to a process when a pathogen that normally circulates in animals crosses into humans and causes infection, often takes place naturally at the points where cultural practices, livelihoods and ecological pressures intersect. Intensive livestock production to meet global protein demand is one driver, but so are practices such as informal slaughter, wildmeat trade or the close cohabitation of people and animals in resource-constrained settings. These realities create conditions where pathogens can more easily cross species barriers.

Where Veterinary Services are limited and surveillance is fragmented, these spillover risks remain invisible until outbreaks occur. Pathogens that escape detection in animals rarely remain confined; instead, they evolve, amplify and eventually reach human populations. Similarly, resistant bacteria emerging in livestock or the environment spread through food, water and trade, undermining treatments worldwide.

Strong animal health systems can counterbalance these risks by acting as a biosecurity shield, building community trust, reducing unsafe practices and providing early warning. Scientific advancements of tools for animal health systems should not only be viewed as technical improvements but rather as critical to bridging global health security priorities with local cultural and livelihood realities, preventing crises before they spread.

Strong animal health systems can counterbalance risks by acting as a biosecurity shield, building community trust, reducing unsafe practices and providing early warning.

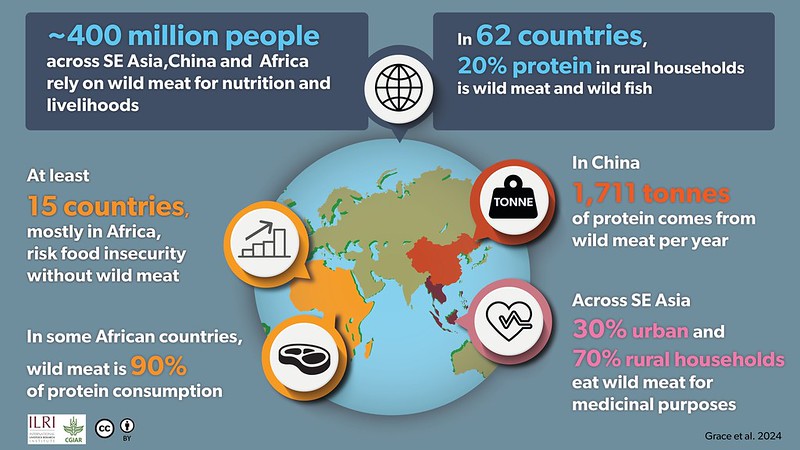

Figure 1. A global snapshot of wild meat and nutrition

In at least 62 countries, wildlife and wild-caught fish contribute at least 20% of the animal protein in rural household diets, providing calories, essential proteins, fats and micronutrients. [6]

Case Studies: Advancing Animal Health Through Surveillance

These health risks are not theoretical. Building on its strategic presence in low- and middle-income countries, which are often at the frontlines of endemic and emerging zoonotic diseases, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) has been developing innovative solutions such as diagnostic tests and vaccine candidates to strengthen animal health systems.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a surge of interest in wastewater-based epidemiology, which examines wastewater to determine the consumption of, or exposure to, chemicals or pathogens in a population. Translating this concept into animal waste surveillance at abattoirs and farms offers a novel lens for early detection at source.

ILRI-led studies in western Kenya and at the wildlife–livestock interface have identified transboundary diseases and revealed the presence of resistant genes in livestock, wildlife, soil and water (unpublished studies). This evidence demonstrates that pathogens and resistance are not confined to clinics but rather circulate silently across ecosystems. By harnessing animal waste as a surveillance tool, the ILRI studies show how low-cost, scalable approaches can generate actionable intelligence for monitoring antimicrobial resistance and zoonotic or transboundary diseases, effectively bridging gaps between the animal, environmental and public health sectors.

Similarly, ILRI’s work on Rift Valley fever (RVF), a mosquito-borne zoonotic disease that devastates livestock herds and causes severe illness in humans, shows how animal health monitoring provides early warning. Ranging from genomic viral evolution studies [2] to ecological and xeno surveillance [3], these show how the virus emerges, circulates and adapts. Genomic studies revealed the diversity of strains and enabled rapid classification of clades, which provides scientific basis for improved vaccines and diagnostics. Similarly, ecological studies have shown how rainfall patterns, mosquito population surges and livestock movement can serve as early signals for impending outbreaks. Detecting patterns in livestock and wildlife before widespread outbreaks occur enables veterinary interventions that reduce risks to human health. RVF stands as a textbook example of prevention as the first line of defence.

Together, these case studies demonstrate that genomic advancements in animal health are global security investments. They prevent zoonotic spillovers, protect food systems and detect threats before they escalate into crises, aligning directly with the vision of One Health security.

Detecting patterns in livestock and wildlife before widespread outbreaks occur enables veterinary interventions that reduce risks to human health. RVF stands as a textbook example of prevention as the first line of defence.

Wildmeat Value Chains: Risk, Culture and Community Engagement

Studies undertaken at the border settlements of Kenya and Tanzania [4] to address disease risk perceptions, as well as wildmeat value chain maps in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area [5], have not only mapped wildmeat value chains and identified key risk points where pathogens could spill over from wildlife to humans, but identified key gaps where food safety regulations, risk communication and protective practices are absent, and where actors prioritise avoiding sanctions over preventing disease.

These findings illustrate that illegal and informal wildmeat value chains are an underappreciated dimension of global health security. Hunting, trade and consumption not only contribute to biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption but also erode the natural ‘sink effect’ that intact ecosystems provide to dilute pathogens. Removing wildlife at scale collapses this buffer, creating greater opportunities for spillover into livestock and human populations.

At the same time, global health security frameworks must acknowledge the cultural and economic realities that sustain these practices. In many communities, wildmeat remains one of the few accessible sources of protein (see Figure 1) and is tied to deeply rooted traditions. Criminalising or stigmatising such practices without providing safe and affordable alternatives risks undermining trust and driving the activity further underground.

Advancing One Health security requires more than surveillance and biosafety; it demands listening, co-designing solutions and aligning global protection goals with the resilience of local communities. Investments in animal health are therefore not only about protecting food systems and rural livelihoods; they are strategic security measures that reinforce global stability.

Main image: ©Oliver Dralam, Getty Images

References

[1] Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990-3. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536

[2] Juma J, Fonseca V, Konongoi SL, van Heusden P, Roesel K, Sang R, et al. Genomic surveillance of Rift Valley Fever virus: From sequencing to lineage assignment. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:520. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/120243

[3] Korir M, Lutomiah J, Bett BK. Ecological factors associated with abundance and distribution of mosquito vectors of Rift Valley Fever virus during an epidemic period in Isiolo, Kenya. Poster presented at: 8th All Africa Conference on Animal Agriculture; 2023 Sept 26-29; Gaborone, Botswana. Nairobi (Kenya): International Livestock Research Institute; 2023. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/132057

[4] Patel EH, Andimile M, Funk SM, Yongo M, Floros C, Thomson J, et al. Assessing disease risk perceptions of wild meat in savanna borderland settlements in Kenya and Tanzania. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023;11:1033336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1033336

[5] Masudi SP, Hassell J, Cook EA, van Hooft P, van Langevelde F, Buij R, et al. Limited knowledge of health risks along the illegal wild meat value chain in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area (NMA). PLoS ONE. 2025;20(3):e0316596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0316596

[6] Grace D, Bett B, Cook E, Lam S, MacMillan S, Masudi P, et al. Eating wild animals: Rewards, risks and recommendations. ILRI Research Brief 129. Nairobi (Kenya): International Livestock Research Institute; 2024. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/152280